Closing Accounts

As the money runs out, hard choices in elder care

DURING THE LAST YEARS OF HER LIFE, MY GRANDMOTHER PAID FROM $4,000 TO $5,700 A MONTH TO LIVE IN FACILITIES THAT SHE NEVER CALLED HOME.

She’s naked from the waist up when we enter the room.

The sheet on her twin-size bed has slipped from the curve of her slight shoulders down to the small of her back—quietly hinting at the soft round flesh just visible beneath the cheap white bedding. She’s curled up in the fetal position, facing the wall. The bare skin of her back is taut and creamy, seemingly youthful despite its age.

I remember this moment only now, months later. At the time, I was distracted by the stench of urine, sour milk and a colostomy bag that desperately needed changing. My grandmother lay there, somewhere between unconsciousness and the painful reality of being awake. Her forefinger was curled up in the cord residents pull when they need a nurse. The tip of her finger was blue, but her fingernail was covered in a dingy brown film—so dirty that I reconsidered hugging her hello. Hovering at her bedside, I wondered how many days of accumulated filth it would take to turn my fingernail that color. The finger moved, slightly, rhythmically. She didn’t speak to us; we couldn’t help her. Instead, she intermittently mumbled what had become her mantra: “God, please help me. Help me please.”

My mom cut up the chicken and biscuits and fed my grandmother baby bites with a plastic fork. I held the straw as she sipped the Sprite. Crumbs and wayward chicken scraps slipped from feeble lips down into her lap, making grease stains on the blanket she always needed to warm her tiny legs.

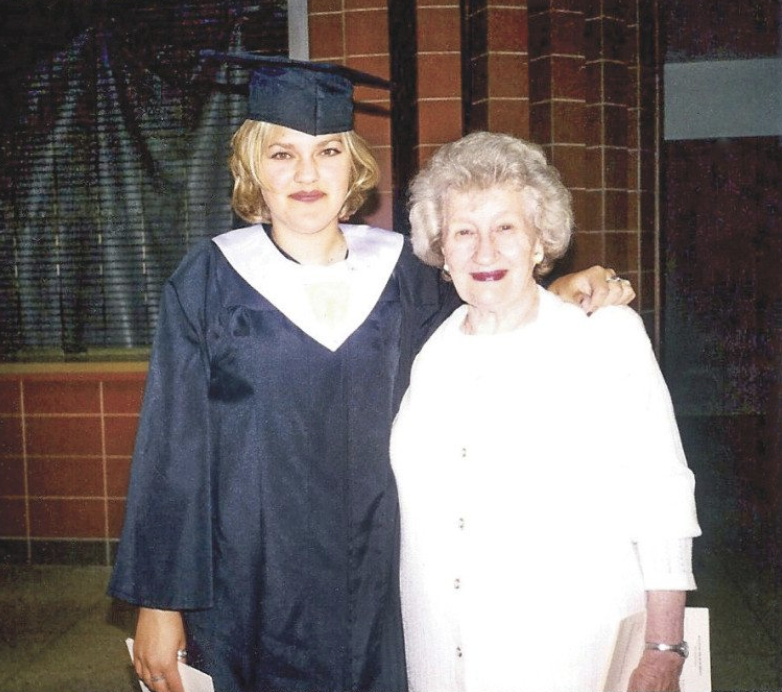

The scene reminded me of feeding my daughter, Amelia, who was then just 2. Food always covered her chubby cheeks and dribbled gently onto her bib, the floor, and usually—somehow—found its way onto my shirt or into my hair. I took care of Amelia the same way my mom was now taking care of her mother. But while Amelia was getting stronger, more independent and more beautiful by the day, my grandmother, now 91, was fading away.

Love is not always pretty. For my mom, it was sad, depressing and, at times, disgusting. But love was always present: in every touch, in every decision, and in every forkful of fried chicken she fed to my grandmother.

This had been my mother’s life for the better part of three years, and it was taking a toll.

I wanted my grandmother to die because I wanted my mother to be able to live. And I hated myself for thinking that, until I realized that my grandmother wasn’t really living; she was just surviving. The person I remembered, cherished and respected was vanishing. And the most painful and saddest part of her life had become the most taxing to sustain.